In our previous posts, we explored how strategic business architecture establishes your transformation “why” and operational business architecture creates your organizational “how.” Now we turn to the third critical layer in our architectural framework: Business Process Design—where abstract visions become concrete workflows that drive organizational change.

When Process Maps Gather Dust: The Design Dilemma

We’ve all seen it happen: An organization invests considerable time and resources creating elaborate process maps. The diagrams look impressive—clean boxes and arrows flowing in logical sequence across the page. Leadership approves them enthusiastically. They’re distributed throughout the organization. And then… nothing changes.

Teams continue working exactly as they always have. The elegant diagrams gather digital dust in shared folders. The gap between documented process and actual work grows wider by the day.

This common scenario reveals a fundamental truth about business process design: The value lies not in the diagrams themselves, but in how they’re created and integrated into the organization’s way of working. The most beautiful process map is worthless if it doesn’t change how work actually happens.

Figure 1: The Process Design Reality Gap

Figure 1: The Process Design Reality Gap

Beyond Documentation: The True Purpose of Process Design

Effective business process design serves a purpose far beyond documentation. It’s not about creating the perfect diagram—it’s about orchestrating the conversations and insights that transform how your organization works. When approached correctly, process design becomes:

- A discovery tool that reveals hidden inefficiencies and opportunities

- A collaboration platform that aligns diverse stakeholders around common goals

- A change management technique that builds buy-in before implementation begins

- A bridge between strategic intention and operational execution

This perspective shifts process design from a documentation exercise to a transformation catalyst—changing not just how processes are drawn, but how they’re conceived, communicated, and activated.

Figure 2: Process Design as Transformation Catalyst

Figure 2: Process Design as Transformation Catalyst

The Conference Room Pilot Approach: Building Processes That Work

The most effective process design methodology doesn’t start with blank diagrams but with structured conversations that bring together diverse perspectives. The Conference Room Pilot approach orchestrates these conversations through a four-step methodology:

Figure 3: The Conference Room Pilot Methodology

Figure 3: The Conference Room Pilot Methodology

1. Executive Visioning Sessions

The journey begins with focused sessions involving 3-5 stakeholders who deeply understand current processes and can articulate a compelling vision for the future. These sessions establish the strategic framework that will guide subsequent process design.

Unlike traditional requirements gathering, executive visioning focuses on outcomes rather than activities—establishing what success looks like rather than prescribing how to achieve it. This approach creates space for innovation while ensuring alignment with strategic objectives.

The key questions these sessions address include:

- What strategic goals must these processes support?

- What outcomes define success from customer and organizational perspectives?

- What principles should guide process design decisions?

- What constraints must be acknowledged and addressed?

These sessions produce not detailed process maps but strategic guardrails that focus subsequent design efforts.

2. Process Flow Drafting

With strategic guardrails established, the next step involves documenting both current state (“as-is”) and future state (“to-be”) process flows. This parallel documentation serves several crucial purposes:

- Current State Analysis: Documenting existing processes reveals pain points, inefficiencies, and workarounds that must be addressed in the future state.

- Gap Identification: Comparing current and future states illuminates the changes required to achieve transformation goals.

- Change Management Preparation: Understanding the magnitude and nature of changes helps anticipate resistance and develop appropriate change management strategies.

The most effective process flow drafting combines multiple perspectives—incorporating insights from both leaders who understand strategic objectives and frontline staff who navigate daily realities. This balanced approach ensures that process designs address both strategic aspirations and practical constraints.

3. Conference Room Pilots

The heart of the methodology lies in the Conference Room Pilot—structured working sessions that bring together 10-20 stakeholders representing diverse functional areas and organizational levels. These sessions transform draft process flows from theoretical diagrams into practical roadmaps for change.

Unlike traditional review meetings where stakeholders passively approve or critique designs, Conference Room Pilots actively engage participants in working through processes step by step—identifying dependencies, raising concerns, suggesting improvements, and building shared understanding.

Figure 4: Conference Room Pilot in Action

Figure 4: Conference Room Pilot in Action

The key activities in these sessions include:

- Walking Through Processes: Simulating how work will flow through the organization, with particular attention to cross-functional handoffs

- Testing Assumptions: Challenging underlying assumptions about how processes will function in real-world conditions

- Refining Interactions: Clarifying how people, systems, and information will interact at each process step

- Building Consensus: Developing shared commitment to process changes through active participation

These sessions don’t just validate process designs—they transform them through collaborative intelligence that no individual designer could achieve alone.

4. Validation and Finalization

The final step involves refining and finalizing process flows based on insights gathered through the Conference Room Pilots. This validation ensures that process designs truly reflect both strategic intentions and operational realities.

Effective validation focuses on several critical dimensions:

- Strategic Alignment: Confirming that process designs advance strategic objectives

- Operational Feasibility: Ensuring that processes can function effectively within organizational constraints

- Change Readiness: Assessing organizational readiness to adopt new processes

- Implementation Planning: Identifying the sequence and support required for successful process implementation

The output of this phase includes not just finalized process flows but also implementation recommendations that bridge design and execution—ensuring that elegant diagrams translate into actual change.

Beyond “Lift and Shift”: Designing for Transformation

A common mistake in process redesign is the “lift and shift” approach—simply digitizing or slightly optimizing existing processes without fundamentally rethinking how work should happen. This approach inevitably limits the transformative potential of your efforts.

Effective process design goes beyond incremental improvement to envision how work could be fundamentally different. This transformative mindset distinguishes between:

- Imperative Changes: Process modifications that are essential for achieving strategic objectives and must be prioritized in implementation

- Nice-to-Have Improvements: Enhancements that offer benefits but aren’t critical for strategic success and can be deferred if necessary

This distinction helps focus limited resources on the changes that will create the greatest strategic impact while maintaining a practical approach to implementation sequencing.

Figure 5: Lift and Shift vs. Transformative Design

Figure 5: Lift and Shift vs. Transformative Design

Making Process Design a Catalyst for Change

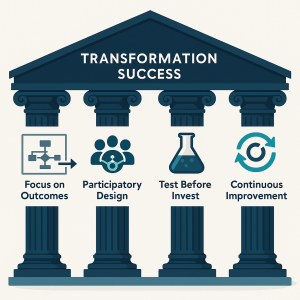

To ensure your process designs drive actual transformation rather than gathering digital dust:

Figure 6: Four Pillars of Effective Process Design

Figure 6: Four Pillars of Effective Process Design

1. Focus on Outcomes, Not Just Activities

Frame process discussions around the outcomes they should achieve rather than just the activities they involve. This outcomes focus keeps designs aligned with strategic objectives and opens space for innovative approaches.

2. Make Design Participatory, Not Prescriptive

Involve those who will execute the processes in designing them. This participation builds both better designs (informed by practical knowledge) and stronger commitment to implementation (based on psychological ownership).

3. Test Before You Invest

Use simulation and pilot testing to validate process designs before full implementation. These small-scale tests reveal issues that might not be apparent on paper and allow for refinement before broader rollout.

4. Plan for Continuous Improvement

Design processes with embedded feedback mechanisms that support ongoing refinement. This approach acknowledges that no initial design will be perfect and creates pathways for evolution based on experience.

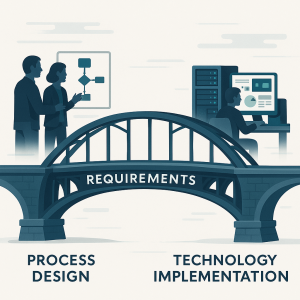

Bridging to Implementation: From Design to Requirements

While process design creates the blueprint for transformation, turning that blueprint into reality requires translating designs into specific requirements that guide technology implementation. In our next post, we’ll explore the fourth layer in our architectural framework: Requirements as Bridges.  Figure 7: From Process Design to Implementation Bridge

Figure 7: From Process Design to Implementation Bridge

We’ll examine how to transform process designs into actionable requirements that connect business needs to technical solutions—ensuring that your transformation delivers tangible value rather than just theoretical improvement.

This article is the third in our “Blueprint for Workflow Design and Business Process Analysis” series—a journey through the architectural layers that transform strategic vision into operational reality.

How has your organization approached process design in transformation efforts? Have you found ways to ensure process maps drive actual change rather than simply documenting the status quo? Share your experiences in the comments below.